UNI REVIEW: Tanghalang Ateneo’s ‘Sintang Dalisay’

“This massive, sophisticated Filipino adaptation of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ proves difficult to perform but feels rich and alive—and honors the late Dr. Ricardo Abad.”

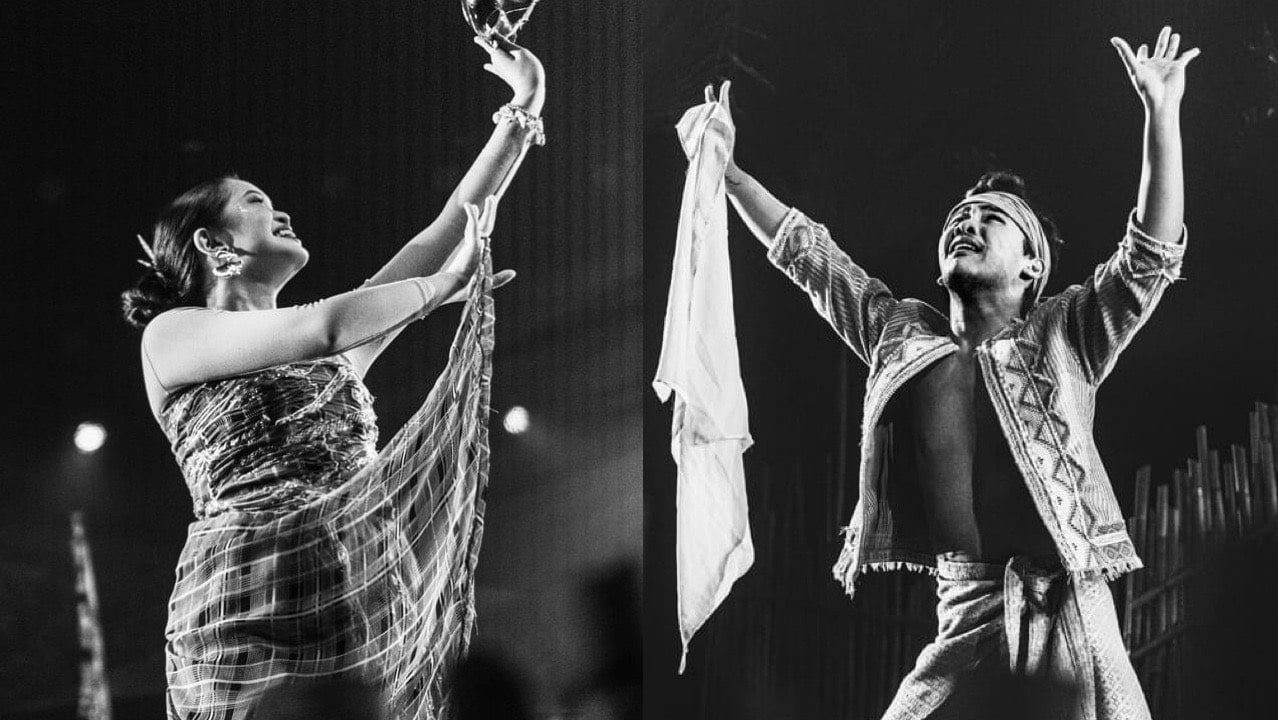

Sintang Dalisay is a work filtered through layer after layer of theater history and performance: a Filipino production of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet set within a Muslim community, drawing from both the play’s 1901 awit adaptation by G.D. Roke and Rolando Tinio’s translation—and done through traditional styles of igal dance and kulintang music from Mindanao. This iteration also honors previous stagings by Tanghalang Ateneo and the late Dr. Ricardo Abad, who originally directed the show in 2011 and who still receives a co-direction credit here.

The resulting production is a massive, sophisticated undertaking that clearly proves difficult to perform with the exact tone it aims for. But perhaps more importantly, it’s a work that feels rich, alive, and in conflict and conversation with itself—not just between the rival Mustapha and Kalimuddin families whose children become romantically involved; but between past and present, emotion and structure, and ritual and performance.

Reverence for Tradition

This adaptation by Abad and co-director/playwright Guelan Varela-Luarca is already an act of negotiation with Shakespeare’s original story. More than just a localized retelling, this play smartly trims characters, sequences, and soliloquies from Romeo and Juliet, to ensure that the performance can feel more like a long, uninterrupted dance. Not only this, the compressed timeline ends up heightening the passion of young love felt by Rashiddin (Karl Borromeo, alternating with Jerome Dawis) and Jamila (Maliana Beran and Mitzie Lao)—something that lesser Romeo adaptations often misrepresent as shallow characterization or mere stupidity.

The show’s direction also attempts to relate that youthfulness to the present, through one scene of anachronistic, topical humor, and certain juvenile comedic gestures that may read as contemporary. These touches aren’t unwelcome, but they momentarily break the spell that Sintang Dalisay already casts so powerfully: for two hours, Varela-Luarca and Abad present this story as a ritual in itself. The musicality of the language, the emphasis on moving on beat, Matthew Santamaria’s intricate choreography (with Brian Sy’s equally elegant fight choreography)—all of these come together in reverence for the traditional forms of performance on display, which need not be unnecessarily exoticized or remixed to be emotional and engaging.

Difficult Performances

Given the highly technical nature of Sintang Dalisay’s performance, its cast has the difficult task of balancing their characters’ emotions with all of the production’s precise rhythmic elements. The primarily student-led ensemble has clearly put in the hard work to capture the latter (especially when functioning as living scenery for the principal actors), but at times at the cost of muffling the former. The play’s movement design and choreography are already definitely infused with emotion, but some interactions between characters can get stuck at the broad and archetypal instead of moving into specific nuances.

Fred Layno as Imam; Photo Credit: Areté

A number of individual performances do manage to reveal more about their respective characters: Fred Layno’s Imam sets a solemn tone at the beginning, and maintains clear sympathy for Rashiddin and Jamila throughout. As hotheaded enemy warriors Badawi and Taupan, Roldine Gabriel Ebrada and Lyle Viray convincingly transform these men back into terrified children when the violence comes to a head. And Karl Borromeo and Maliana Beran are able to convey a fragility and uncertainty in their sudden romance, especially when their characters consummate their love in a stunning, wordless synchronized dance. It’s here where the casting of students feels entirely purposeful.

A Generous Reimagining

Beyond these younger actors, it becomes easy to forget that this is a university production, due to its massive scale. Production designer Tata Tuviera (after the late original designer Salvador “Badong” Bernal) has put together a breathtaking set all adorned in bamboo: an open central area, platforms leading to a common second level, a walkway extending out into the audience, and an inner chamber at the heart of the stage. There is both height and depth here, with D Cortezano’s lights bringing either a divine glow or bursts of disruptive violence. Gwyneth Dianne Zenarosa and Paul Adrian Martinez’s colorful costumes fill the spaces with personality and give volume to all the choreography.

Lyle Viray as Taupan; Photo Credit: Areté

However, this Sintang Dalisay is at its most impressive when it comes to its music. Within that inner chamber, an ensemble of musicians (half of whom are members of the world music collective Anima Tierra) drive the story forward through Edru Abraham and Jayson “Dyandi” Gildore’s dazzling combination of traditional percussion, strings, woodwinds, and vocalizations layered seamlessly by sound designer John Robert Yam—even as the musicians respond to the action like a Greek chorus. It’s this connectedness between music and drama that ultimately animates the play into something that seems to be performed as an act of communal storytelling. As a way of reimagining Shakespeare, it’s generous, inviting, and entertaining—all qualities that the late Dr. Abad would have been proud to see in a piece of theater for his students.

Comments