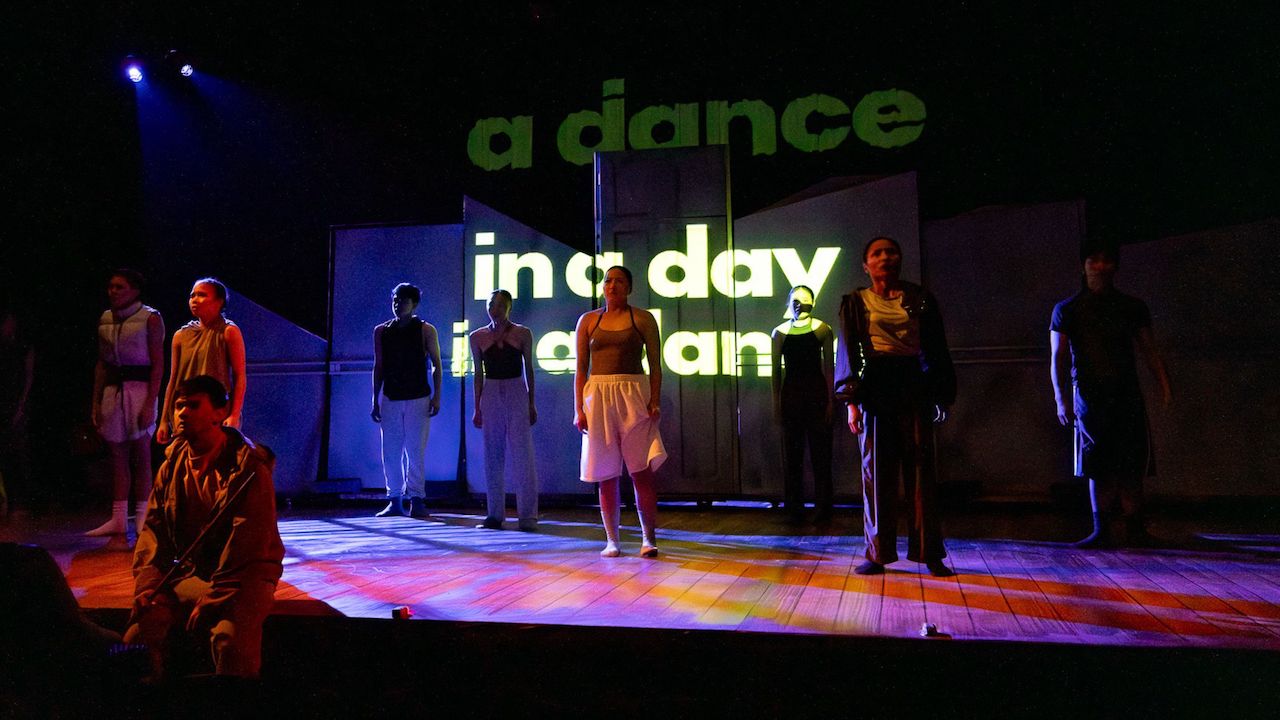

REVIEW: Mari Dance Turns Rehearsal Tension into Riveting Dance Theater in ‘A Dance in a Day in a Dance’

If the newly-minted contemporary company Mari Dance had a regular season and a well-funded board, it could be a welcome disruptor in a dance scene that has grown staid with commercial formulas and, on the other end, artistically pretentious or shallow contemporary works.

Founded by Japhet Mari “JM” Cabling, Mari Dance keeps its boundaries clear: projects that please clients, and choreographies that feed artistic impulse. The latter can be risky in a market where many still find dance arcane, prompting large companies to favor the same reliable, ticket-selling repertory. In the European postmodern spirit he favors, emotion fuels the motion — but that emotion must be grounded in strength and technique. His sharp sense of narrative and feel for stage dynamics give his works a dramatic pull that keeps the viewer engaged.

Last weekend, Mari Dance debuted its first artistic concert, “A Dance in a Day in a Dance,” featuring some of Cabling’s landmark works. Director Mikko Angeles cleverly weaves the pieces into the frame of a rehearsal day, centered on a run-through of “Lihim ni Lea (Lea’s Secret),” a 30-minute work based on Augie Rivera’s children’s book about incest and a girl’s way of coping. Wika Nadera’s movable set pieces double as doors, partitions, and walls fitted with ballet barres. The pacing and rhythm of shifting these modules become a choreography of their own. The other dances serve as the inner stories of the performers who inhabit this studio.

“A Day in a Life” begins with a dancer leaving through a door, fully dressed, and returning moments later, she leans into a deep Graham hinge. With body tilting back from the knees but held firm at the core, it is a moment that captures exhaustion not just of the body, but of spirit. The gesture repeats through other doors, performed by different dancers, each tracing the same arc— energized on the way out, depleted on the way back. The scene opens into the studio, where dancers stretch and warm up until the choreographer enters, disciplinary stick in hand, a relic of old-school training.

Cabling introduces a striking motif. Dancers begin in a yoga-like cobra position, then see-saw into a reverse arch, balancing on their chests as legs and hips lift toward the ceiling. From there, they fold into a seated swastika position before spiraling upward into a turn. The choreographer makes them repeat this phrase over and over. It becomes a punishing cycle of control and submission that mirrors the emotional rhythm of the entire work.

Arvy Dimaculangan’s sound design, built on pulsing rhythms, the hypnotic counting and monologues, heightens both the drive of the choreography and the fraught tension between dancers and the choreographer who pushes, provokes, and belittles them.

INSIDE THE DANCER’S MIND

When the choreographer leaves the studio, another tension builds between the dance captain, KJ Canata, and the rest of the cast. Each dancer, opinionated and overeager, begins to interpret the choreography in their way. Though bossy, Canata, moves with fluidity; his strength comes from ease, not force. Displeased, the choreographer strikes a dancer with his stick and expels him from the rehearsal. The scene shifts to “I Wanna Say Something,” a symbolic piece about unspoken emotions and group solidarity.

In an earlier interview, Cabling explained that this section unfolds in the mind of the rejected dancer. The lead, Michael Barry Que, dressed in silver, embodies the dancer’s thoughts as he reaches for a suspended microphone, hesitates, then lunges toward it as the haunting humming in “Cow Song” by Meredith Monk and Colin Walcott wafts the air. As the violins in Alexander Balanescu’s “Pursuit,” dancers gather behind him, rolling their shoulders, linking hands to form a circle before breaking off into duets and small groups, each exploring its own rhythm as the microphone swings overhead. A female dancer in matching silver represents the higher mind. She tries to hand him the mic, but the two struggle in a tense pas de deux until she lets go, sending it spinning around the stage.

Michael Que with the company in “I Wanna Say Something”; Photo Credit: Mari Dance

The lead’s restrained movement contrasts with the ensemble’s restless energy. They lift him toward the microphone as it sways like a pendulum, until he finally grasps it. The piece ends with rolling shoulders, turning movements, and a quiet triumph as he holds the mic aloft.

The program notes cite “Reply 1988,” a Korean television series set in the 1980s, as an inspiration. Its dance scenes with rhythmic, expressive movement and emphasis on attitude and camaraderie resonate here. Cabling captures its essence but gives it his stamp. His choreography, though grounded in contemporary technique, draws from breakdance—kicks from arm balances, leg swipes on the floor, and backspins with legs slicing through the air like windmills.

Back in the studio, the dancers rehearse pas de deux lifts as the set for “Lihim ni Lea” is being prepared. The choreographer scolds them for sloppy partnering and awkward transitions, then calls on Katrene San Miguel, in Lea’s pink costume, and uses her to demonstrate a series of lifts taken from the piece itself.

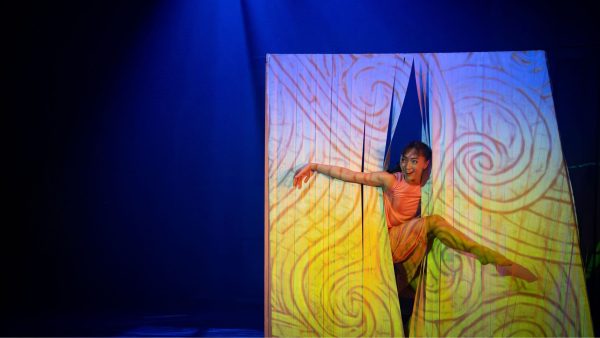

LEA’S SECRET

“Lihim ni Lea” tells of a girl who imagines herself able to pass through walls—her body becoming intangible as she moves through the rooms of neighboring tenants. Onstage, this is shown through a wall made of garters, where Lea’s limbs emerge and disappear as she peeks out from different openings. At school, she tries to repeat the act but instead repeatedly bumps into the windows, a behavior that puzzles her teacher. Her fantasy, the piece reveals, is a coping mechanism for sexual abuse by her father, played by the choreographer. Her imagined ability to move through walls becomes a metaphor for escape. Dimaculangan’s music sustains the tension and deepens the mood.

Katrene San Miguel in “Lihim ni Lea”; Photo Credit: Mari Dance

The climactic duet between father and daughter unfolds as a study of control and submission. Cabling explores the imbalance of power or patriarchy through physical levels—Garcia’s character towering, pulling her hair, dragging her backward, pushing her down. The movement grows darker as he rolls over her bent back, lifts her body like a feather from the floor, and hovers close to her body in a suggestion of violation. It’s a disturbing yet precisely rendered scene, a test of both performers’ sensitivity and strength. As the father crosses over her crouched form, he strokes her face, then drags her away. On the opposite side of the stage, the teacher and the OFW mother sit on the floor, their gestures evoking messages of turmoil and the distance that has fractured the family. A police siren wails; the father surrenders. The OFW mother rushes in and revives her daughter.

The piece gains power from the shifting set design, which reconfigures into different condo units. Dancers in black, wearing small props and accessories to suggest furniture, neighbors, or dancing lovers, animate these transitions. San Miguel is mesmerizing—not just for her agility and strength but for the emotional range she brings to Lea, moving from innocence to fantasy, from fear to recovery. Garcia distinguishes his portrayal of the father from that of the choreographer seen earlier; here, he is less authoritarian than manipulative, which makes the menace more chilling.

REJECTING CONVENTIONS

As a transition, Lea bids her father goodbye. He has changed costume, and returns as the choreographer, carrying his trademark stick. Now alone, he seems to enter an internal dialogue in “Nothing Special.” His body loosens into grooves and quick footwork until he confronts a younger version of himself, portrayed by Jenris Garcia. What follows resembles contact improvisation—the two listen through touch, responding to each other’s weight, momentum, and energy. Yet beneath the spontaneity lies a carefully composed structure that builds a narrative of self-recognition. In the final image, the younger self lifts the older man, carrying him as if in release. The choreographer finally smiles.

L-R: Jenris Garcia, Al Garcia in “Nothing Special”; Photo Credit: Mari Dance

Al dances with a firm, muscular presence, every gesture measured and weighted. His movements anchor the space, while Jenris counters with a smooth, almost liquid strength. His transitions are effortless, his phrasing more fluid than forceful. Together, their contrast—one sculpted, the other seamless—creates a dialogue between tension and release, power and restraint.

However, this introspective piece may be an acquired taste for Filipinos that prefer pure and “loud” entertainment. The relative quietness of “Nothing Special” plays against the emotional charge of the earlier dances, which smoldered with conflict and theater.

“Bent,” by contrast, returns to heat and tension. It’s a duet between a woman and her best friend that rejects gender conventions, set to the explosive “Laughing Track” of the Crookers duo and “Paper Birds” by the Parachutes. The score’s screams and shouts mirror the struggle between attraction and restraint. He advances; she resists. Their movements unfold like a dance between desire and denial—cartwheels over the body, lunges, collapses, and quick recoveries that blur the line between wrestling and embrace.

Sheanne Montesclaros and Arnel Sablas in “Bent”; Photo Credit: Mari Dance

A towel becomes their recurring prop and metaphor. At first it conceals, draped over bodies in gestures of shame of mixed-orientation sex. Then it transforms. Wrapped around the head, the towel turns them into sisters, tied as a cape, they play superheroes. In role playing, the towel becomes the man’s baby bump, and later a “baby” cradled with mock tenderness. In a reversal of roles, she carries him in an over-the-shoulder lift. The duet ends with both lying side by side, the towel covering these besties like a shared blanket.

Sheanne Montesclaros and Arnel Sablas perform the piece with humor, strength, and total ease. They move without inhibition, playful one moment, sensually charged the next, balancing irony with affection and inhabiting the alpha female and the gay BFF respectively.

SEAMLESS SCENES

Back in the studio, the dancers, dressed in fatigue-inspired pants, wield long staffs as if training in martial arts. When the choreographer steps in to strike a dancer, the moment shifts from rehearsal to ritual. The sequence recalls bojutsu, the Japanese martial art that uses a staff or cane as both weapon and extension of the body—for striking, sweeping, thrusting, blocking, and dodging a partner’s attack. The dancers’ movements are circular and fluid, alternating between aggression and flow. For the choreographer, the staff becomes not only a symbol of authority but also a tool for reconciliation—with his dancers, and perhaps with himself.

Al Garcia and the company; Photo Credit: Mari Dance

The production moves seamlessly from scene to scene, its pacing tightly knit. Cabling’s choreography demands acting intelligence, technical precision and physical power. His dancers execute multiple pirouettes with ease—nothing looks forced. Though grounded in contemporary dance—body layouts, contractions and releases and spirals, his vocabulary folds in elements of hip-hop: rippling torsos, b-boy floorwork, fast footwork and sudden drops to the ground.

What makes Cabling’s choreography come alive is how he plays with height, balance, and weight. His dancers fall into new shapes that spring from tension and release. The movement flows quickly—strong, athletic, and fully engaged. He also explores body isolations, especially in the torso—rippling, twisting, and folding in ways rarely seen onstage. These details give his movement texture and depth, expanding what the body can say without words. His movement language blends discipline with instinct; moments of looseness are always caught by control. The result is dance that feels immediate and human—demanding in skill yet charged with joy and presence.

In his group sections, the dancers weave in and out of each other’s paths, creating shifting patterns that feel both spontaneous and tightly organized. Doing justice, the Guang Ming College dancers perform with a raw, unselfconscious energy that makes their movement feel both disciplined and alive.

The props do much of the storytelling. Aside from the microphone and towel that reveal the dancers’ relationships, the moving sets of doors, windows, and ballet barres carry their own meaning. The doors and windows suggest the constant movement between the outside world and the dancer’s inner life—between exposure and retreat, connection and solitude. Their shifting positions show how situations and emotions can change without warning. The ballet barres, meanwhile, stand for discipline and control—the fixed routines that dancers return to no matter how chaotic life gets. Together, these elements show how a dancer learns to move between freedom and structure, instinct and order, all within the same space.

Audiences, accustomed to glaring floodlights in many dance productions, may find D Cortezano’s lighting subdued. Yet its subtlety is the point. The illumination never competes with the choreography; it reveals. Faces are lit in natural tones, giving breath to the movement rather than flattening it. Joyce Garcia’s video projections complement this restraint, deepening the visual field without overwhelming it. The result is a production that breathes—where light, image, and motion move as one. Director Mikko Angeles ties it all together, moving seamlessly from the dancers’ studio banter and bursts of rehearsal chaos to the layered dances and finally a hopeful ending that feels earned.

Tickets: P1,800, P1,500

Show Dates: October 10-12, 17-19, 2025

Venue: Doreen Black Box Theater, Areté, Ateneo de Manila University

Running Time: approx. 1 hour 10 minutes

Company: Mari Dance

Creatives: JM Cabling (artistic director and choreographer), Mikko Angeles (director), Wika Nadera (set designer), D Cortezano (lights designer), Arvy Dimaculangan (sound designer), Joyce Garcia (video projection designer), Carlo Valderrama (costume designer)

Dancers: Al Garcia, Katrene San Miguel, Michael Que, Sarah Samaniego, Jenris Garcia, Arnel Sablas, Sheanne Montesclaros, Evan Asuela, KJ Canata, Yna Arbiol, Abegail Turiano, Sophie Serdan, Pauline Angeles, Alf Catana, Carl Jeoffrey Lato

Comments